Nairn’s London #12

The Gun, Coldharbour

THEN: You will know a bit about East End topography by the time you find this one. Coldharbour is a tiny loop road off Preston’s Road, which is the eastern entry to the Isle of Dogs, and the Gun is at the southern end of it. Good hunting. It is a good friendly dockland pub that has neither been irreparably spoilt by the brewers nor irreparably taken up. The special thing, unsuspected from inside, is at the back – through the Saloon in summer, down the passage past the Ladies and Gents in winter. For the Gun is a riverside pub, and the particular bit of the riverside is the sharpest part of the curve around Blackwell Point. Nowhere is the muddy horizontal excitement of the Thames more urgent than here, framed in a tiny terrace, the curvature making sure that the maximum amount of swift-running water stays in the view.

NOW: Every bit the good friendly dockland pub of Nairn’s day. Some miracle, because its now run by a big brewery: Fullers. Its still a great bolthole, but with Canary Wharf a stones throw away, the city boys have moved in. There’s even a shuttle service that runs between the pub and the offices. The Thames view is still as urgent, as violent, but the O2 (or the millennium dome, depending on your age) now sits proudly across the way, waving from the other side.

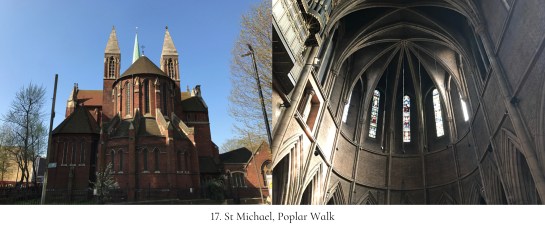

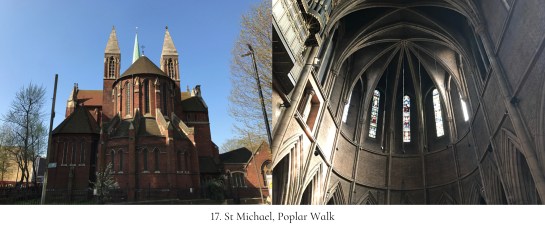

Nairn’s London #17

St Michael, Poplar Walk

THEN: Perfection is rare anywhere and perfection due to a reasoned balance rather than an inspired leap is maybe rarer still. So North Croydon is worth a visit if you don’t look at any other buildings for the rest of the year. J. L. Pearson in his later buildings had the rare gift of being able to take the hackneyed theme of a late-thirteenth-century church and restate its essence exactly, with complete natural sweetness. That a hundred people had tried before and failed makes no difference; any achievement as good as this is beyond relative values. Perhaps the best of all his churches: red brick outside, pale yellow brick inside, apsed and vaulted, burning with a completely stead, cool flame. Off the south transept, Person built a chapel, a church within a church, with a complete octagon of columns – a devotional toy. Stand inside the octagon, and look out: every relationship between the multitude of arches, vaults, shafts and mouldings is completely harmonious. It is a Gothic cathedral, re-created without magic by the century which discovered evolution.

NOW: Easy to find but hard to see – it took two weekend trips to Croydon and several hours of waiting before its doors opened for me to look inside. Even then, I had to hurriedly survey it to avoid the beginning of mass. Outside, from the east, its a dead ringer for Hogwarts. On the inside, it’s a space built to inspire. Grand but not imposing, cool but not cold. If you’re along this way and you find the doors open, be sure to pop your head inside.

Nairn’s London #16

Dulwich Art Gallery

THEN: One of Soane’s most original, least satisfying designs. For once, the miraculous inventiveness is not connected up to an emotional purpose. It remains an intellectual solution, a beautifully played game of chess. It was severely damaged in 1944, and the restoration, though exact, is oddly unsympathetic. It emphasised the aloof man-hating part of Soane which was dominant in the design anyway. So Dulwich is a great curiosity, not a masterpiece. The collection is completely conventional but of high quality: the kind of selection that would appear in any big country house but without the same distressing proportion of duds. And occasionally amongst the talent there is a real masterpiece like Watteau’s Fête Champêtre, where the familiar portentous melancholy is screwed up to an unexpected pitch by flecks and gleams of light on the grey dress of the central figure.

NOW: Immaculately preserved, its probably in better nick today than it was in the sixties. On approach, the building does little to warm your cockles. But the gardens are lush, and there’s a busy cafe to the right of the gate. Inside, the space lacks character, forcing full attention upon the collection itself. I searched for Watteau’s Fête Champêtre, but I’ve a feeling they’ve sold it. No matter, there are plenty of other old masters here and its well worth an afternoon.